A History of our Tiles

In the 13th century, abbeys, monasteries, and palaces featured tiled floors, often intricate mosaics. These evolved into inlaid or ‘encaustic’ tiles—made by pressing patterns into clay, filling them with contrasting slip, and glazing with lead oxide. Fired at 1000ºC, impurities in the glaze produced warm, rich hues.

The Encaustic Tile

By the 16th century, encaustic tiles fell out of fashion, but the 18th-century Gothic Revival revived interest. In 1835, Samuel Wright experimented with reproducing medieval tiles, later selling his patent to Chamberlain & Co and Herbert Minton. Minton perfected the process, supplying tiles for Temple Church in London and collaborating with architect A.W.N. Pugin on the Palace of Westminster.

As demand grew, manufacturers like William Godwin refined production, eventually introducing dust-pressing in the 1860s. This method compacted powdered clay under high pressure, enabling multi-colored inlaid designs. On the continent, a similar technique used thin metal frames to separate colors, producing softer edges.

By 1900, encaustic tile production thrived across Europe, particularly in France, Belgium, and Spain, even as it declined in the UK. Today, original encaustic tiles are being restored and relaid, their beauty enduring for over a century.

Carreaux de Ciments

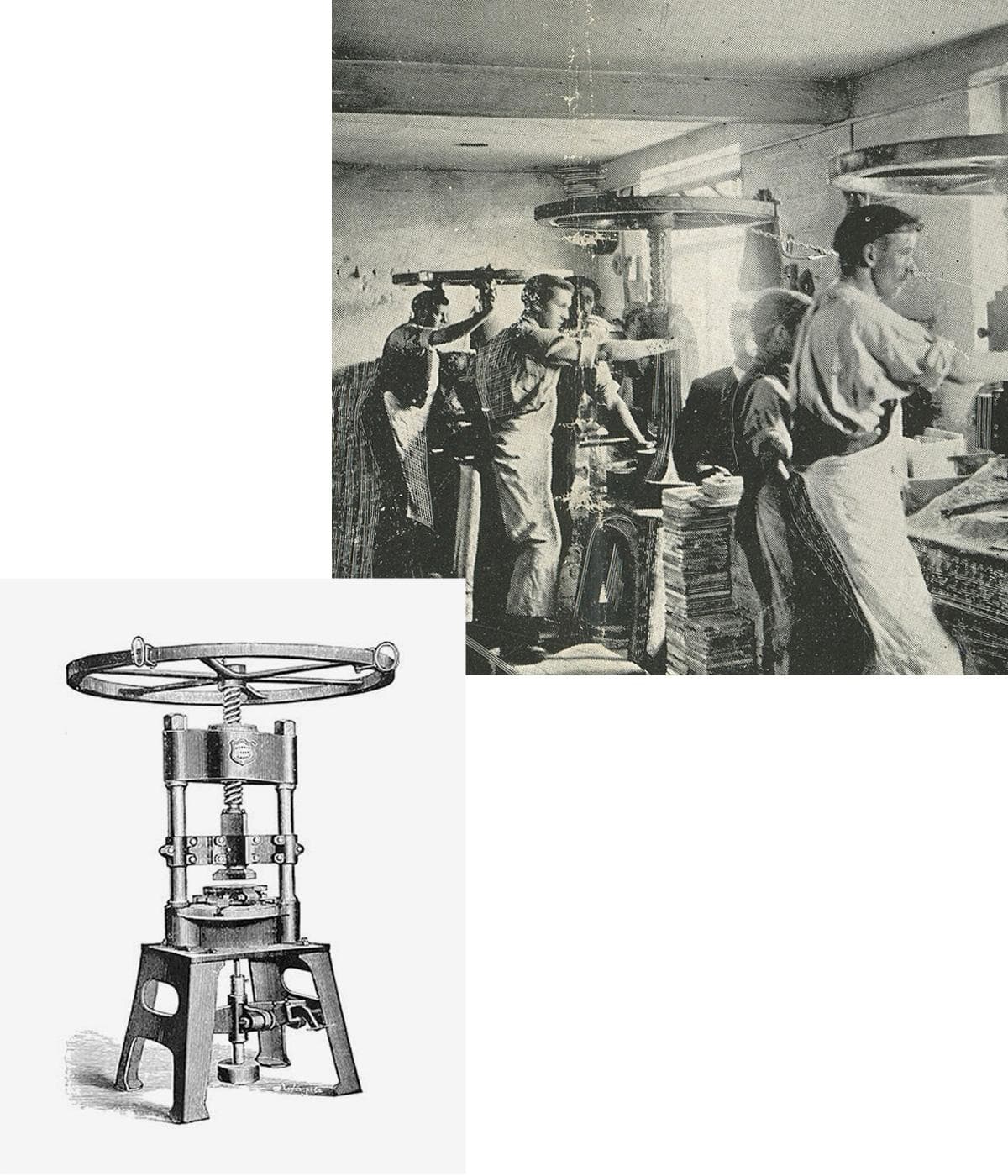

Emerging in France (1890–1910) as a cheaper alternative to ceramic encaustic tiles, carreaux de ciments were made from colored cement and marble dust poured into brass molds. Unlike fired ceramic tiles, these were left to cure in humid conditions, preventing surface fissures.

Typically larger and thicker (up to 20cm square, 2kg each), carreaux de ciments featured bolder, simpler designs due to material constraints. While ceramic tiles allowed intricate 1mm-wide details, carreaux required at least 5mm, resulting in more geometric, classical patterns.

Both tile types remain highly sought after, valued for their durability and aesthetic appeal.